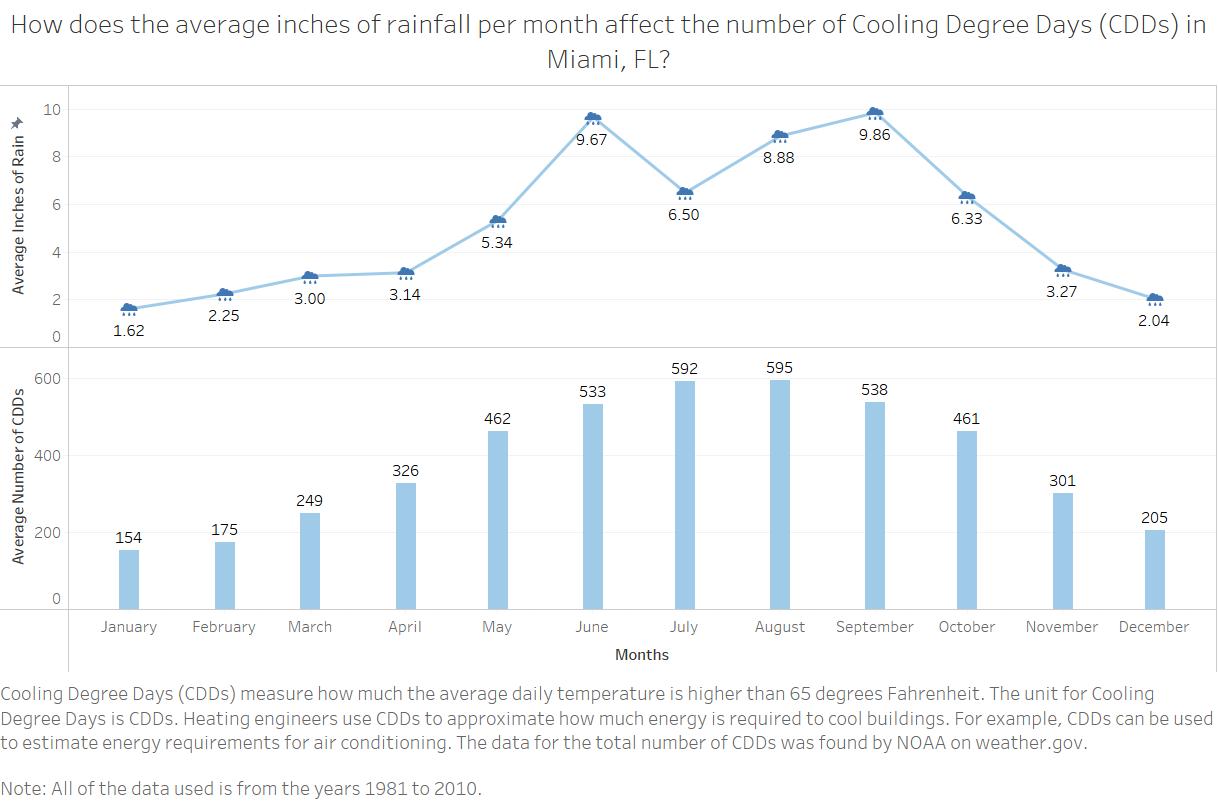

How does the average inches of rainfall per month affect the number of Cooling Degree Days (CDDs) in Miami, FL?

The Data

- The

miami_climate.csvhas also been provided for you here. - This CSV is a mix of data from the US Climate Data and NOAA’s online weather data.

Why Miami, FL?

I chose to highlight Miami because Florida is known to have a lot of rain, and when I looked at the data that fact was reflected, as Miami had the highest rainfall of the six cities I looked at (San Diego, San Fransisco, Chicago, Houston, New York City, and Miami). Some other characteristics that make Miami interesting is that Florida typically has lots of humidity because of its rainfall and proximity to the ocean. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) when there is more moisture, which could come from rainfall and other bodies of water, the amount of humidity increases.

How is this helpful?

I chose CDDs because heating engineers use this unit to approximate the energy needed to cool a building to 65 degrees Fahrenheit. This is not only useful for heating engineers, but also for consumers. If they found their energy bill was higher than expected they could use CDDs as a good measurement of comparison from before the bill was issued to see what caused the energy increase. As stated in the visualization, CDDs can be used to estimate energy requirements for air conditioning. Not only does air conditioning keep your home comfortable, but it turns out that running air conditioning can act as a dehumidifier. There are other benefits to running air conditioning like preventing mold and mildew and filtering allergens from entering your home. If these things are important to you or if you just want to stay cool, then you might be tempted to run the air conditioning more. CDDs are a great tool to figure out how much energy you should use to keep your home comfortable. This way you will always know the perfect amount of energy needed and your bill will stay low!

Visualization Design Choices

To plot my visualization I used Tableau and the miami_climate.csv. A large design choice was having a line chart on top of a bar chart. I debated having a dual axis, but I felt that by doing so it would be difficult for viewers to read the data. The dual axis highlighted the correlation of average inches of rain and the total number of CDDs, but I thought for clarity, it would be better to have one chart on top of the other. For both sections of my visualization I chose to use the color blue. Blue is web safe and is clear for everyone to read. Furthermore I thought the blue color was reminiscent of cooling and water. Something else I added was my caption, which makes my visualization more clear because it defines Cooling Degree Days and specifies what time the data came from (1981-2010). My visualization was exported using Tableau, so the size is large and readable, which is important because there is a lot of data being conveyed. For both graphs, I chose to have my time on the x-axis, which is “Months” because time is an independent variable. I also chose to order my x-axis by having the months appear in the order of the year (Jan, Feb, Mar, Apr, …). I thought it would be more natural to see the months in this order than, say, alphabetically.

The top half of my visualization is a line chart. I chose to use a line chart because this graph type effectively communicates changes that happen over time. The line mark helps portray the progression of values, which is the average inches of rainfall. Something whimsical I added was inspired by Nigel Holmes. To be a little more memorable I made the points on my line chart little rain clouds. I thought it was a really cute addition, which made me happy and also makes my graph more relatable, as most people associate a rain cloud with precipitation. The color of the rain clouds is a darker blue so the viewer can more easily see the shape. I added labels to my line chart because I wanted the values to be as clear as possible for the viewer. Something to note is that I rounded my averages to two decimal places.

For the bottom half of my visualization I chose to use a bar chart. I chose to use a bar chart because unlike the line chart we are not trying to show something continuous. The bar mark is good for groups and discrete values, which my data reflects. I also added labels to my bar chart because I wanted to stay consistent. I did not do any rounding, these were the values provided to me by NOAA. Both of my y-axes are labeled to help emphasize the values are the average inches of rain or average number of CDDs instead of another transformation (like total or difference). This was on purpose so there would be no question about what was on the graph. I chose the scales for both y-axes. I thought the scale from 0 to 11 and the scale from 0 to 670 also portrayed the average inches of rainfall and average number of CDDs well. If I had chosen to increase either scale there would be too much white space, which I did not want because I thought it might make the graph harder to read and might flatten out my data.

Interesting Observation and Note

Finally, something I would like to note about my data visualization that might be misleading or confusing is how there seems to be a strong correlation between average inches of rainfall and Cooling Degree Days except for in July. In July the average inches of rainfall is surprisingly low for the average number of CDDs. I hypothesize this could be happening because July is in the middle of summer. Summertime is usually the hottest time of the year. CDDs are impacted by rainfall, but also temperature. As CDDs are the energy required to cool a building down then when it is really hot, independent of rainfall, it is possible to accumulate CDDs. My conclusion is that rainfall impacts CDDs, but has a weaker “weight” compared to pure high temperatures. As humans, we feel that the higher the humidity, the higher the temperature, which causes a higher heat index. A higher heat index makes us want to turn the air conditioning on and cool off. This means the average inches of rainfall affect CDDs because it causes humidity, but is not the strongest factor.

Bibliography:

US Department of Commerce, NOAA. Climate, NOAA’s National Weather Service, 3 Mar. 2022, www.weather.gov/wrh/Climate?wfo=mfl.

US Department of Commerce, NOAA. “What Are Heating and Cooling Degree Days.” National Weather Service, NOAA’s National Weather Service, 13 May 2023, www.weather.gov/key/climate_heat_cool.

US Department of Commerce, NOAA. “Discussion on Humidity.” National Weather Service, NOAA’s National Weather Service, 13 June 2015, https://www.weather.gov/lmk/humidity/.

Daikin. How You Can Use Your Air Conditioner during the Rainy Season, 10 Nov. 2023, www.daikin.com.my/tips/how-you-can-use-your-air-conditioner-during-the-rainy-season/.

Energy Star. Climate and Weather, Aug. 2020, p. 9, www.energystar.gov/sites/default/files/tools/Climate_and_Weather_2020_508.pdf.